Pictured above is the Civil Defense storage building at the Elk City, Oklahoma Municipal Airport in June 2018. After the Cold War ended in the early 1990s, the city’s fallout shelter supplies, including the ones featured in this exhibit, were transferred from their former shelters to the storage building, where they remained until their removal in 2020. Courtesy of Landry Brewer.

Living 'Under a Nuclear Sword of Damocles:' Elk City's Fallout Shelter Supplies

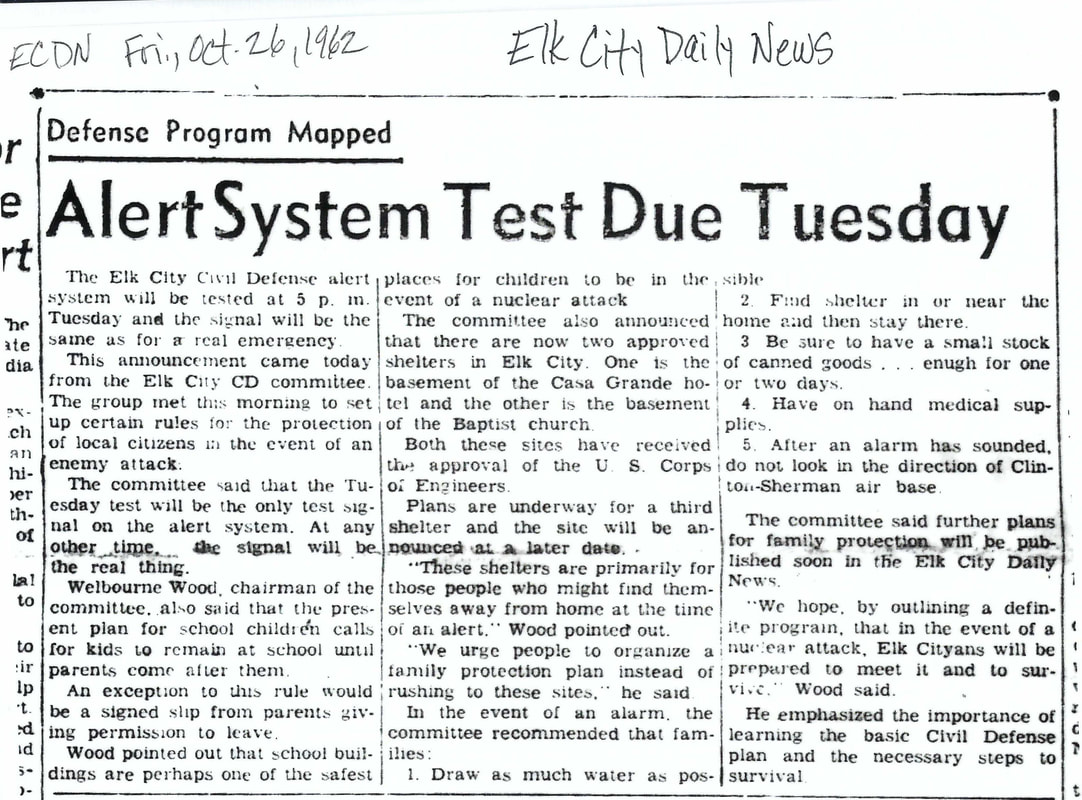

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 16-29, 1962, marked the closest point at which the U.S. and Soviet Union ever came to using nuclear weapons in the Cold War (1947-1991). Foremost in the U.S. nuclear arsenal at the time were thermonuclear warheads attached to intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of striking cities 9,000 miles away in 45 minutes. Each warhead wielded approximately 4 megatons of explosive power (equivalent to 4 million tons of TNT), making it about 255 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, killing over 90,000 people in 1945. Twelve of these warheads and their ICBMs, the SM-65F Atlas Missiles, were each housed in an underground silo in one of 12 towns located within a 40-mile radius of Altus Air Force Base, making the entire area a potential target for Soviet nuclear attack. Another possible target was the Clinton-Sherman Air Force Base in Burns Flat, a Strategic Air Command facility located 14 miles southeast of Elk City. On October 26, 1962, the Elk City Civil Defense Committee announced the Casa Grande Hotel and First Baptist Church basements as federally approved nuclear fallout shelters.

Featured in this exhibit are water drums, sanitation kits, radiation detectors and other U.S. government-issued supplies that were stored in Elk City’s fallout shelters from the 1960s to the 1990s. These items were available to the public in the event and aftermath of a nuclear strike. This exhibit is partly a remake of an earlier exhibit curated by Landry Brewer, a Bernhardt Assistant Professor of History at the Southwestern Oklahoma State University college at Sayre, and author of Cold War Oklahoma (2019), who donated most of the items displayed here to the Elk City Museum Complex.

To qualify as a public fallout shelter, a space had to accommodate a minimum of 50 people, include one cubic foot of storage space per person, and have a radiation protection factor of at least 100—meaning that a person would be at least 100 times safer from radiation inside of the shelter than outside of it. The U.S. Department of Defense provided supplies to local governments which assumed responsibility for stocking the shelters in their area.

Pictured above is the Casa Grande Hotel in Elk City, Oklahoma, c. 2010s. Constructed in 1928, the building once served as the largest luxury hotel along Route 66 between Oklahoma City and Amarillo, Texas, and hosted the U.S. “66” Association’s National Convention in 1931. During the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, the U.S. Corps of Engineers approved the hotel’s basement as one of Elk City’s first two public fallout shelters. The Casa Grande Hotel was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1995 and still stands today. Courtesy of Landry Brewer.

The Office of Civil Defense issued food guidelines for federally stocked Cold War fallout shelters. Though 1,500 calories consumed per day was considered sufficient to sustain daily activity for an individual in the early 1960s, the government believed that healthy people could function for the maximum confinement of two weeks under sedentary conditions on 700 calories per day. Four food items were chosen to stock fallout shelters: the “Survival Biscuit,” the “Survival Cracker,” the “Bulger Wafer,” and the “Carbohydrate Supplement.”

These Carbohydrate Supplement cans stocked an Elk City fallout shelter from the 1960s until the 1990s. All food items were packaged separately in sealed cans with an estimated shelf life of between 5 and 15 years.

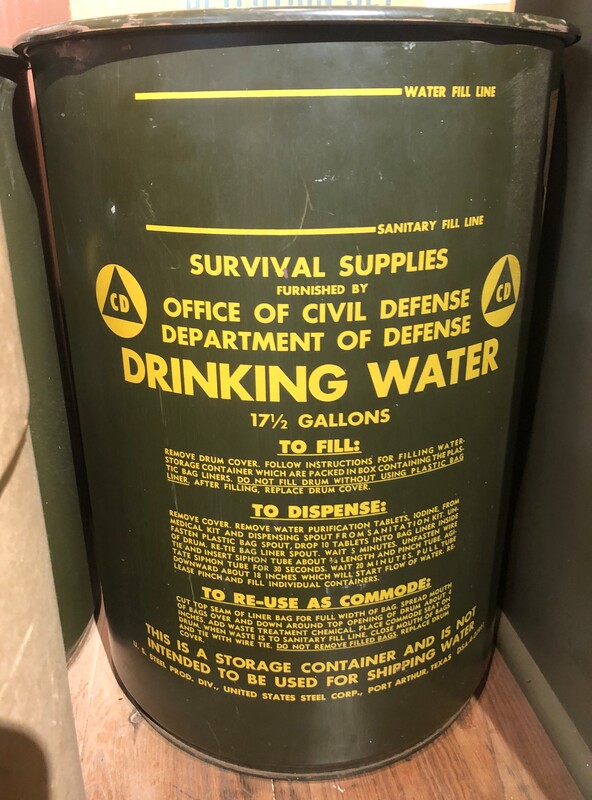

Water drums provided by the federal government during the Cold War for public fallout shelters—such as these drums that stocked an Elk City shelter from the 1960s until the 1990s—held 17.5 gallons of water. Each drum was intended to provide five people with one quart of water a day for up to two weeks.

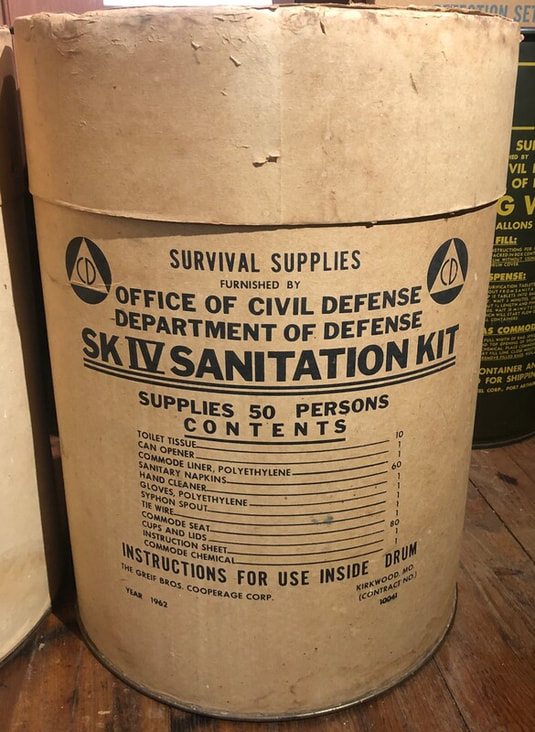

The federal government also stocked public fallout shelters with food, medical kits, sanitation kits and radiation detection equipment. The two sanitation kits and radiation detection device shown here stocked an Elk City fallout shelter from the 1960s until the 1990s.

The federal government also stocked public fallout shelters with food, medical kits, sanitation kits and radiation detection equipment. The two sanitation kits and radiation detection device shown here stocked an Elk City fallout shelter from the 1960s until the 1990s.

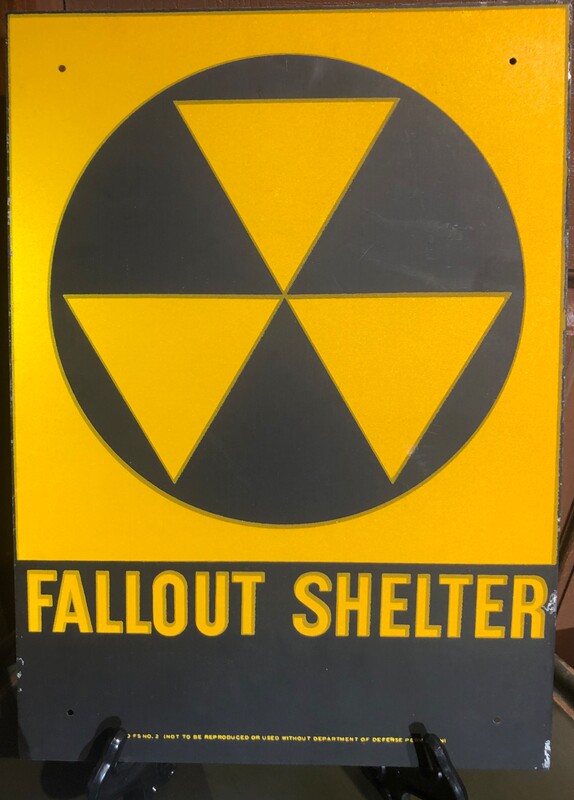

In December 1961, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) created the federal fallout shelter sign like this one here. The DOD required all buildings with federally approved shelters to have these signs placed outside their entrances.

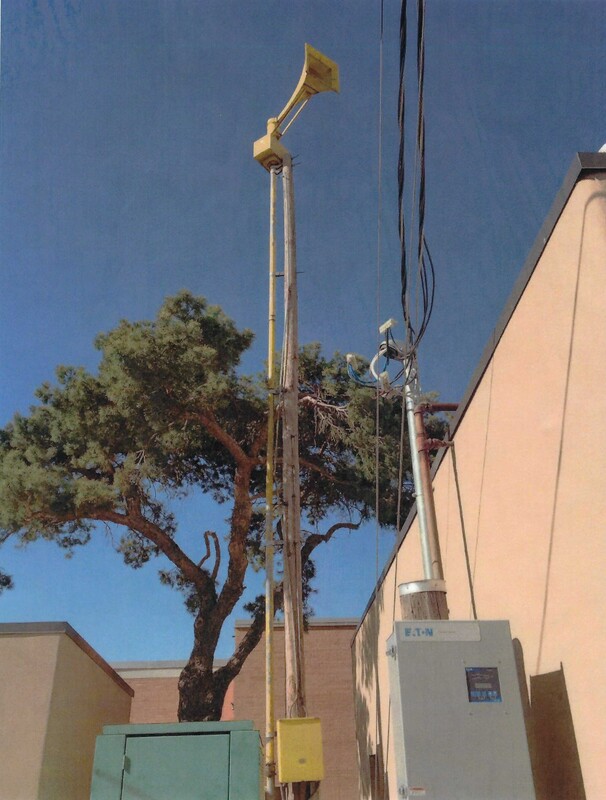

The federal emergency Thunderbolt Siren for civil defense was developed in the early 1950s. Elk City installed several yellow Thunderbolt Sirens during the Cold War for nuclear attack warning. Elk City’s remaining Thunderbolt Sirens are used solely as storm sirens today, warning residents of an imminent tornado instead of an imminent nuclear missile attack.

This Thunderbolt civil defense siren timer was used in Elk City during the Cold War. The silver “TEST” button operated the siren as long as the button was pushed. The blue button was the “ALERT” signal which operated the siren in a steady ON mode for 3 minutes. The yellow button is the “ATTACK” signal which operated the siren in an on-off or wavering mode for 3 minutes. The black “CANCEL” button stopped the timer’s control of the siren signal while the timer continued to run to the end of its cycle.